AI in Education - Some food for thought

What are we supposed to do about Generative AI in (mathematical) education?

Many of us have been wrestling with it over the past few months. I certainly don’t have a definitive answer, but it’s a topic that demands we share what we’re thinking and what we’re seeing. If anything, it may bring a felt and needed opportunity to finally be able to rethink and reshape the way our education is organized. We discussed this in less uncertain times both in It’s Not Just Numbers and various episodes of Degrees of Freedom, our podcasts on mathematics and education respectively.

It helps to start with a realistic view of the technology. I like Andrej Karpathy’s take on it: think of using an AI less like consulting an oracle and more like “asking the average data labeler on the internet.” That framing cuts through a lot of the hype and re-grounds the conversation: these are statistical models trained by imitation, not logical reasoning machines.

As you probably know if you follow this rarely updated blog or if you follow me on social networks, I’ve been tinkering with these tools for quite a while. With time I settled to simple, tedious tasks where I can easily spot if something is wrong: generating ALT text for an image, getting a first draft of some Python code translated to JavaScript for a web demo, drawing pages for our kids, things like that… It’s a utility, a shortcut for boring work I could do myself and that I can easily check.

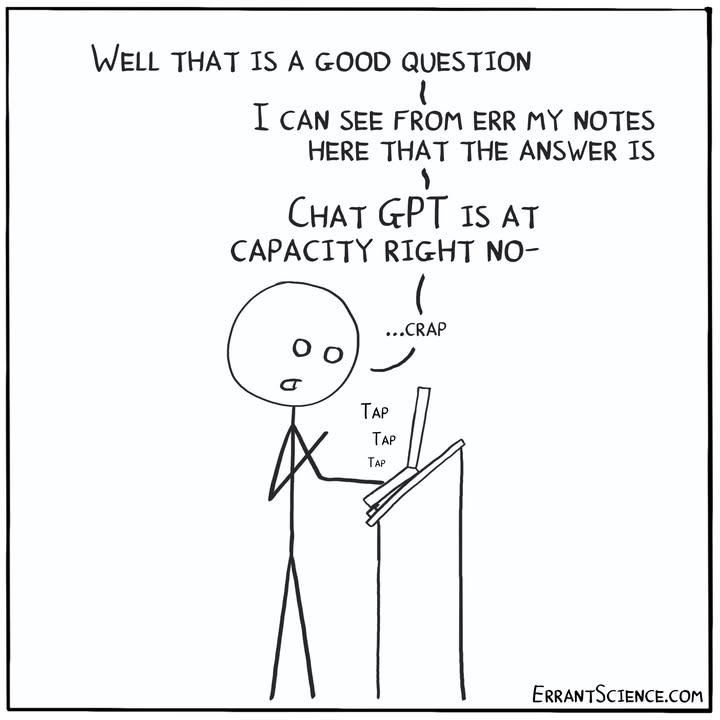

The real difficulty comes when we think about our classes and the use most of our stdents seem to be engaging with. Recently, I’ve started seeing homework submissions with what, citing a couple of colleagues, we started calling “froofs”: things that look a lot like proofs, using the right words and symbols, but are fundamentally flawed or nonsensical. What worries me isn’t really that the answer is wrong, but that the entire process of mathematical thinking has been bypassed. The struggle, the dead ends, the (smaller and larger) breakthroughs, those are where the learning happens.

A slick, confidently incorrect “froof” robs a student of that entire experience and, worse of all, of the learning itself. At this point I can name many instances also of students asking questions about strange definitions or assumptions on concepts in our courses; when asked, they often say they found them in the “AI-generated” summaries of the material, and somehow they often never bothered to check the actual course materials.

This is not just a problem of students using these tools to cheat; it’s a fundamental issue with how they engage with the material. And it worries me but also makes me want to do something to steer the students in a better direction. By this I don’t want to say, a priori, that these are bad and useless tools. And I think that outright banning them is not the answer. I understand the impulse: these tools can be misused, and they can undermine the very foundation of what we do as educators. But the dilemma remains: as a partial user myself, I think there can be useful ways to engage with those tools, but I cannot ignore the risks and the problems they are causing us.

By the way, we should also not ignore the many ethical and environmental issues that come with these technologies (that, when not ignored, seem to have even shadowed the similar discussion concerning cryptocurrencies, instead of joining that club and increasing the societal pressure), but these are for another post. And, besides, I think it is ingenuous to believe that these tools are not here to stay; perhaps with a more constrained scope and less ubiquitous scope, once the hype fades (why on earth do we need those useless summaries in every search?), and hopefully way cheaper to run (both economically and environmentally). I found the research paper “Every wave carries a sense of déjà vu: revisiting the computerization movement perspective to understand the recent push towards artificial intelligence” quite revealing in exploring future scenarios for the technology by taking a more sociol ogical perspective.

But let’s close this side note and go back to the original point. Looking back, I am aware of positive experiences: for instance, I had a student using LLMs to generate new exercises form a batch of old ones, so that they could work on them, check their understanding and try to figure out the correctness of the exercises themselves. This was an excellent way for them to learn, practice and formulate clearer questions to ask to me in class or at tutorials. But this kind of critical use, in my experience, is the exception rather than the norm. So there are, after all, useful ways to integrate these tools in learning. And you may already have played with them yourselves, and realized this.

I have been pondering a lot how could I rethink my courses to try and benefit from the situation. I’m not interested in an arms race of AI detection; it feels like a losing battle and a miserable way to interact with students. This semester, I’m trying an experiment: I’ve made homework ungraded. The idea is to lower the stakes and, hopefully, remove the incentive to get the perfect answer, allowing more scope for exploration and feedback. The goal is for homework to be a place for genuine practice. We then use class and tutorial time for peer-feedback, which I hope encourages them to engage with the material and each other’s reasoning more critically. The actual assessments of understanding are moved fully to the midterm and final exams.

I don’t know if this is the “right” answer. It’s just one attempt to adapt to a new reality. It feels more productive than simply banning the tools or pretending they don’t exist. But it’s an open question, and I suspect there are many different approaches being tried out there.

To share a couple of other ideas from my colleagues, some are requesting students to explicitly sign pledges to not use LLMs or, at least, to detail how they used them in their work. The hope is at least to make students reflect on their use of these tools and, maybe, its implications, while also making it clearer that they are expected to engage with the material themselves. This also opens up an interesting conversation about academic integrity and cheating, but it is a rabbit hole I don’t want to go down right now.

Others, more expert machine learning researchers, are using the internal design of LLMs to their advantage, rewriting their homework with paraphrases and keywords from popular culture, like character names and scenes from cult movies or famous TV shows, that are predominantly found on movie reviews rather than on STEM exercises. This way, they make it harder for students to simply copy-paste answers from LLMs or the web, while also making the homework more engaging and fun. LLMs are very sophisticated statistical parrots after all, and specific names and references steer them immediately away to specific bubbles of information (movies and TV shows in this case, rather than solutions of STEM exercises). This is a clever way to use the limitations of the technology to our advantage, and it also makes the homework way more enjoyable for students. Of course, the big caveat is that this requires a lot of effort to design the homework, and it may not be feasible for all courses or all instructors.

What are others trying? How are these tools showing up in your classrooms? I’m genuinely curious to hear other experiences and ideas. In the meantime I have collected my thoughts, experiences and experiments, as well as some literature and nice tools, in a set of slides that we used to start the discussion at our department. I share them below since a few colleagues have been asking for them. Please, feel free to contact me to share your experiences!